Why is our Foundation named after Robert Schuman?

Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity

Robert Schuman Declaration, 9th May 1950

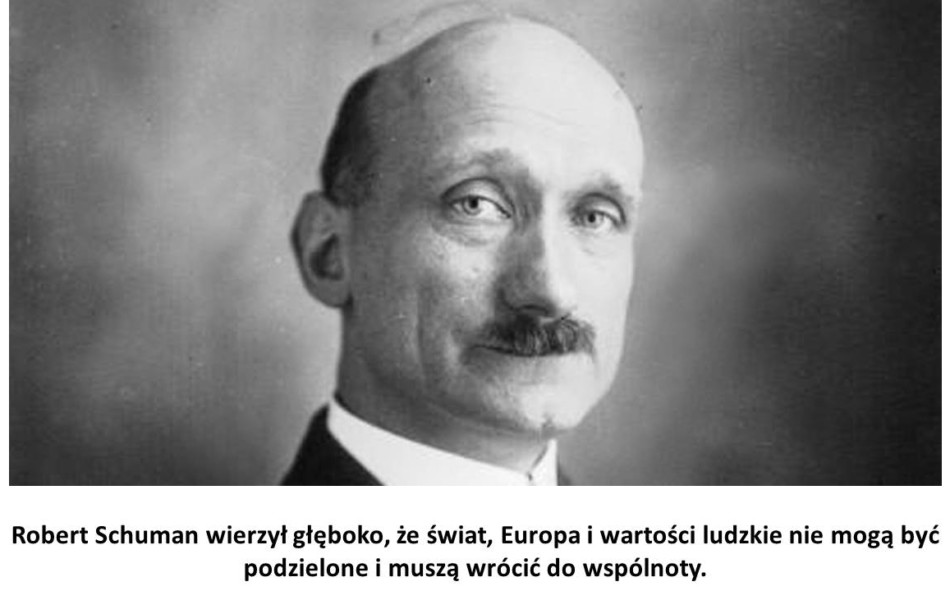

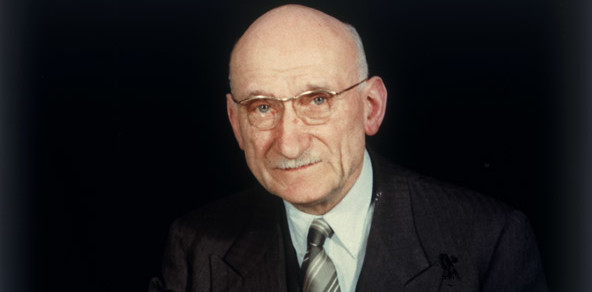

Robert Schuman (1886-1963), Lorrainer and Frenchman, lawyer, twice Prime Minister of France, Finance Minister and Foreign Minister, a key figure in post-War Europe, known as the Father of Europe. He is best known to the public for his Declaration of 9th May 1950, commonly referred to as the Schuman Plan: five years after the end of the Second World War, Schuman proposed to the former enemies – Germany and France – that they should work closely together and establish a community based on heavy industry; an idea that changed the course of the history of the continent and the world. Robert Schuman’s beatification process is now underway at the Vatican.

„We like to give politicians labels. Visionary. Realist. Statesman. Pragmatist. They all fit Schuman, but perhaps the most appropriate in his case is to point out that he was a man of dialogue” – writes Anna Radwan in the introduction to the book Schuman and his Europe (published by the Schuman Foundation).

How did the Schuman Declaration come about?

On 9th May 1950, in its solemn declaration, the French Government chose a united Europe. A Europe saved from Hitlerism and from Communism, a Europe freed from fratricidal and futile battles, a Europe that had boldly and decisively committed itself to a common path, a Europe that was the guarantor of prosperity, security and peace – this is how Robert Schuman recalled the announcement of the Plan (For Europe, 2004, ZNAK).

That day, in the Salon de l’Horloge of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, two hundred journalists waited anxiously for Robert Schuman. Finally, in a trembling voice, the Foreign Minister read out the foundations of a project that would change the history of the continent and the world. Why was this project, which at first appeared to be a proposal for the establishment of a gigantic international coal and steel cartel, so groundbreaking?

The time when Schuman announced his programme was exceptional. Just after the war, Europe was exhausted, and still divided into two opposing camps – East and West. There were as yet no common European institutions linking the disparate nations. Although the idea of a European community was emerging among politicians, with the creation of interstate customs unions and the Council of Europe for democracy and human rights, many ordinary people knew the other nations only from past wars, seeing their neighbours as past or present enemies, or simply as occupying armies. The history of Franco-German conflict was not confined to the First and Second World Wars; it had been going on almost continuously for centuries.

At that time, the sense of European identity was based on the shared experience of the Second World War and – especially in the West – on the fear of communist expansion, triggered by events such as the coup in Czechoslovakia or the Berlin blockade (1948). Even among European political leaders convinced of the rightness of strengthening international ties, there was no consensus. Two visions for the future of Europe clashed: national and federalist.

Supporters of the former (including wartime British Prime Minister Winston Churchill) advocated cooperation at the level of national governments, which would retain their sovereignty. The federalists (e.g. Belgian Prime Minister Paul-Henri Spaak), on the other hand, wanted to introduce common institutions of a supra-state nature, such as a pan-European legislature and executive. As can be seen, today’s European Union, with its parliament and unified legislation, is closer to the latter vision. This is also how Schuman thought of Europe.

The Monnet Plan

The idea of economic cooperation between France and Germany already had a basis and was not a completely irrational idea – there was a climate for change in Europe. The project we all know as the Robert Schuman Plan was in fact conceived by Jean Monnet (1888-1979), a French official of the League of Nations, Commissioner for Economic Planning.

Already during the Second World War, Monnet had drawn up a plan for Franco-German reconciliation based on the joint management of coal and steel – raw materials that were then associated with an arms race. He kept it in a drawer, waiting for the right moment to win the favour of the international community and, above all, the favour of the French authorities. Recalling this period, Jean Monnet wrote: I needed someone who had the power and the courage to use it to bring about such a great change unexpectedly. A conference of Western European Foreign Ministers was scheduled for 10th May 1950 – the opportunity came about to present the French initiative at this forum.

Monnet’s idea fitted in perfectly with the ideas of the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman (1886-1963), a politician associated with the pro-European, Christian Democratic party of the Popular Republican Movement. Schuman’s policies had two main goals: Franco-German reconciliation and securing peace throughout Europe. Schuman’s vision had its source in his deep faith, in a philosophy of Christian personalism that emphasised respect for human dignity, democracy and human rights. Personal experience also played an important role in shaping his views – Schuman was brought up in Luxembourg, studied in Germany and made a political career in France. He described himself as a Luxembourger by birth, educated in Germany, a Roman Catholic by conviction, and a Frenchman at heart.

Monnet was aware of Schuman’s personal experience and political credo. So when the Prime Minister of the French Republic, George Bidault (1899-1983), ignored his idea, Monnet immediately turned to Schuman. Once the latter had accepted Monnet’s idea, he acted swiftly. He was able to sway the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967) to the project even before the French Government and Parliament were aware of it.

The Americans, too, became aware of the new European economic concept even before it was publicly announced. Dean Acheson (1893-1971), the U.S. Secretary of State, supported the initiative, which was not immediately obvious. Acheson recalls in his memoirs that he was initially very concerned that the Monnet-Schuman initiative was an attempt to set up an enormous coal and steel cartel and commit an unforgivable sin of violating the laws of competition and market freedom that Americans cared so much about.

After a few days’ work on Monnet’s draft, Schuman presented it to the public, proposing – just five years after the end of the war – that the former enemies, Germany and France, should work closely together. A declaration issued on 9th May 1950 proposed the creation of a European community based on heavy industry, joint management of coal mining and steel production. This was to be overseen by a specially created Joint High Authority.

Partners, no longer enemies

Although the geographical area of the agreement was relatively small, comprising after all only the Ruhr and Saarland, its political significance was enormous. In order to fully appreciate the stature, uniqueness, as well as the courage of this project, it is worth realizing that just after the Second World War the possibility of solving the German problem by destroying its industry and turning it into an agricultural country was seriously considered.

For this reason alone, the idea of inviting Germany into international cooperation was extraordinary. It was a breakthrough to put permanent enemies in the role of collaborators, and bringing more countries into it strengthened the Western bloc politically, which in a Cold War situation could not be overestimated.

The creators of the Plan wrote about it this way: Placing coal and steel production under common management will ensure the immediate establishment of common foundations for economic development, the first stage of the European Federation, and will change the destiny of these regions, long condemned to the manufacture of the weapons of war of which they have been the longest victims.

In addition to Germany and France, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Italy and the United Kingdom were invited to join. Italy and the Benelux countries quickly accepted the project. Britain remained sceptical and only joined the European structure in the 1970s.

Difficult beginnings

Obtaining the approval of the French parliament was not easy. For the French communists, the idea of drawing Germany into a common European project was inconceivable, also because it would strengthen the Western bloc. As for the Gaullists, the idea of a European community seemed unacceptable because of its supranational nature. In the end, the project passed in the second reading, thanks to the support of the Socialists.

One did not have to wait long for the effects of the Schuman Plan – two years after its announcement, the six-state European Coal and Steel Community came into being, followed in 1957 by the European Economic Community and Euratom – the foundations of the European institutions that still operate today.

“Pragmatism in economic decisions was to serve the creation of a community of states and nations, citizens and people. The founding fathers of the European community had the wisdom to postulate gradual changes, not seeking spectacular revolutionary transformations, but changing what had to be changed in order to preserve what had to be preserved,” wrote Professor Bronisław Geremek in the introduction to For Europe (ZNAK 2004).

* An extract from the text prepared by Anna Radwan-Röhrenschef on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Schuman Declaration.